The Science Behind Bacterial Growth: Why a Single Cell Becomes a Colony

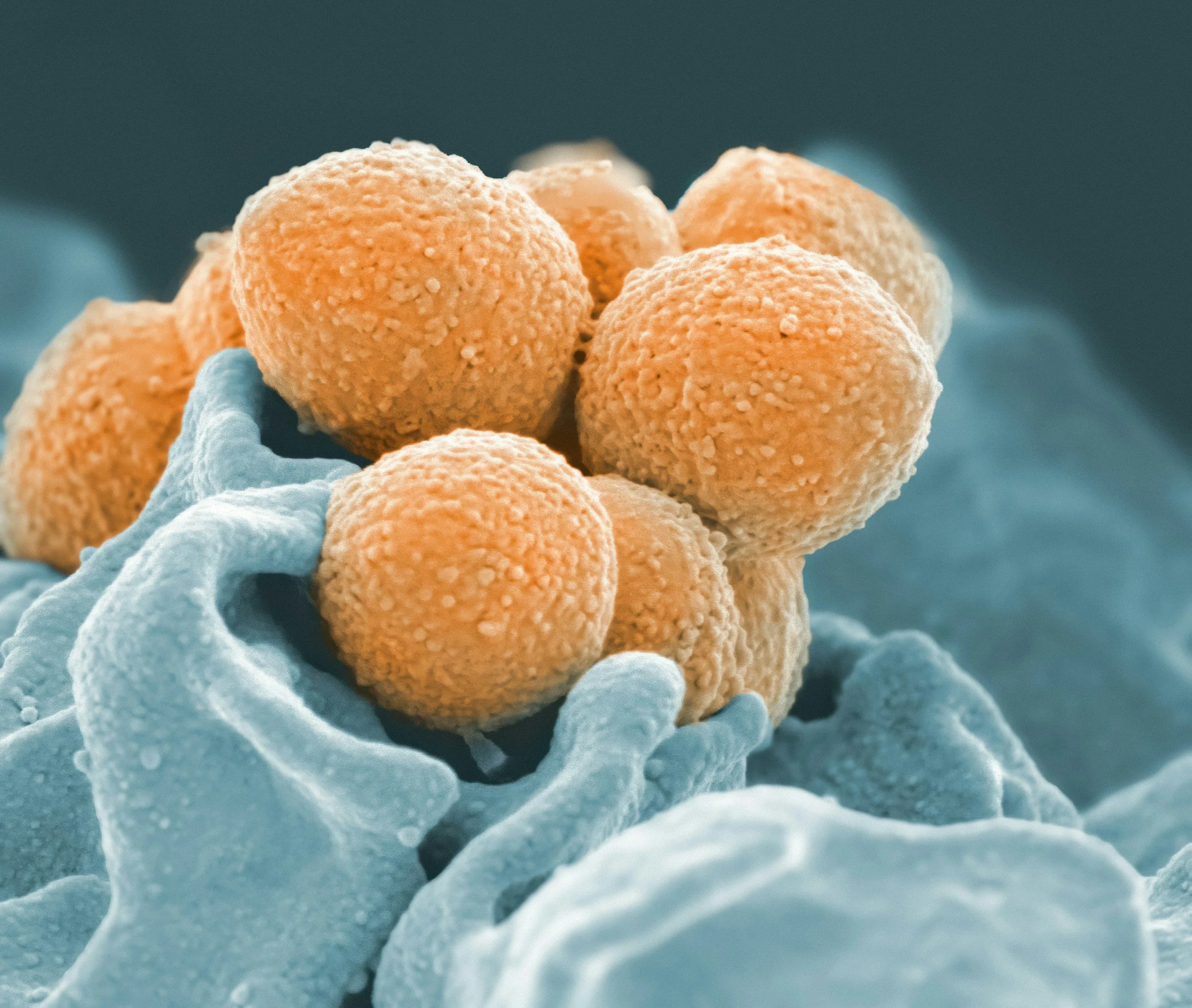

One bacterial cell does not seem dangerous. One cell of Escherichia coli is invisible to the naked eye, weighs less than a picogram, and seems utterly insignificant in the vastness of food or human body.

Yet that single cell is a sophisticated biological entity with the potential to become a problem rapidly. Understanding bacterial growth is understanding one of the most important principles in food safety, fermentation control, and disease prevention.

Binary Fission: Life's Simplest Multiplication

Bacteria reproduce through binary fission, the simplest form of multiplication in the biological world. A single cell replicates its DNA, grows to roughly twice its size, and then divides into two identical daughter cells. Each of these cells, under appropriate conditions, repeats the process.

This creates a growth pattern that defies human intuition. Most people think about growth linearly: one becomes two becomes three becomes four. But bacteria grow exponentially: one becomes two becomes four becomes eight becomes 16 becomes 32.

The mathematical formula is simple: N equals N0 times 2 to the power of the number of doublings. If you start with one cell and it doubles six times, you have 64 cells. But if it doubles 20 times, you have more than a million cells. Double 72 times and you have enough bacteria to cover the Earth thousands of times over.

Growth Rate: The Doubling Time

Different bacteria grow at different rates depending on the organism and the environment. The growth rate is measured as doubling time (td), the time required for a population to double.

For Escherichia coli under ideal laboratory conditions (37 degrees Celsius, optimal pH, unlimited nutrients), the doubling time is approximately 20 minutes. This means in one hour, a single E. coli cell becomes eight cells. In two hours, 64 cells. In eight hours, more than 16 million cells.

Different organisms have different doubling times. Listeria monocytogenes, a pathogenic bacterium that grows in refrigerators, has a doubling time of 20 to 30 minutes at 4 degrees Celsius (cold temperature). Lactobacillus plantarum, a beneficial fermentation bacterium, has a doubling time of 3 to 6 hours at 22 degrees Celsius depending on the specific strain and substrate.

Temperature has a profound effect. The same bacterium at 4 degrees Celsius grows much more slowly than at 37 degrees. Roughly, for every 10-degree increase in temperature, the growth rate doubles (up to the organism's optimum). This is why refrigeration extends food shelf life: it slows bacterial growth dramatically.

The Four Phases of Growth

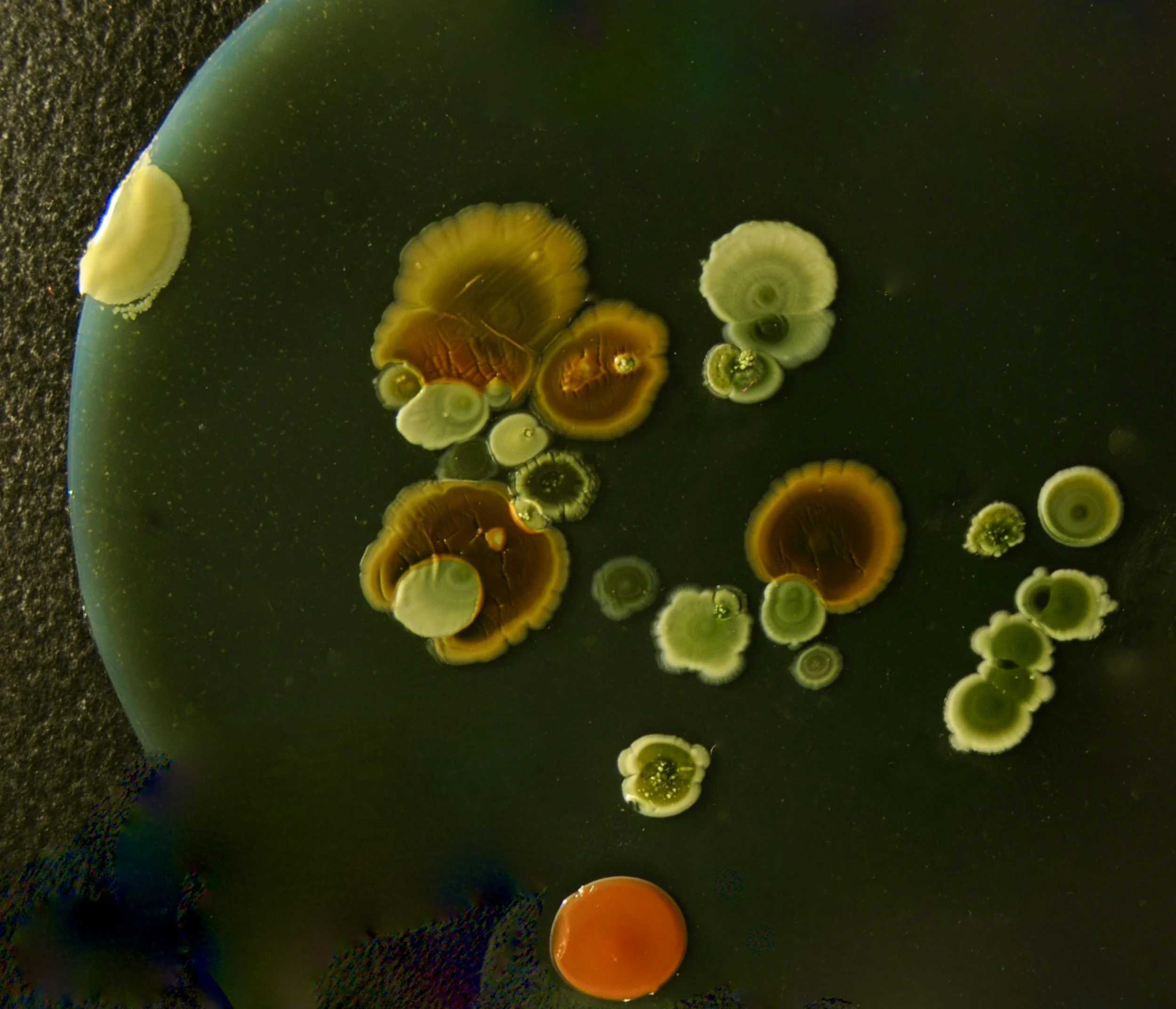

When bacteria are placed in fresh medium (food or growth medium), they do not immediately begin reproducing at maximum rate. Instead, they follow a predictable pattern visualized as the growth curve.

Lag phase is the initial adaptation period. Bacteria have just arrived in a new environment. They lack enzymes suited to the available nutrients. They must synthesize new ribosomes and transcription machinery. During this phase, no cell division occurs. The cells may even shrink slightly as they burn energy without reproducing. Lag phase can last from minutes to hours depending on how similar the new environment is to the previous one.

Exponential (log) phase is when conditions become ideal. Nutrients are abundant, waste products have not accumulated, and temperature and pH are optimal. Cells divide at their maximum rate, all cells are healthy and metabolically active, and the population doubles at regular intervals. This is the phase you want in fermentation: rapid, predictable growth of beneficial bacteria.

Stationary phase occurs when nutrients become depleted or waste products accumulate to toxic levels. The growth rate slows to match the death rate. The population plateaus and remains at a high level but does not increase. This is common in fermentations: the fermentation proceeds rapidly until sugars are depleted, then the population stabilizes.

Death phase (also called decline phase) occurs when growth slows below the death rate. More cells die than reproduce. The population decreases, sometimes dramatically. In food systems, this represents spoilage and degradation of food quality even if the original spoilage organisms die off.

The Deceptive Nature of Exponential Growth

An illustration makes exponential growth clear. Imagine a single algae cell in a lake that doubles every single day. The cell coverage looks insignificant for weeks. On day 50, the algae covers only 12.5 percent of the lake.

The question: on what day does the algae cover 50 percent?

The intuitive answer seems to be roughly day 87 (50 percent minus 12.5 percent equals 37.5 percent, divided into daily doublings). But the correct answer is day 57, just one week later.

Why? Because 12.5 percent requires only two more doublings to become 50 percent. The exponential nature means the final doublings contain more growth than all previous phases combined.

This principle is critical for food safety. A contaminating bacterium at 100 colony-forming units per gram (CFU/g) seems trivial. Food becomes noticeably spoiled at approximately 1 million CFU/g. The calculation is simple: 100 to 1,000,000 requires going through approximately 10,000 times more bacteria, or about 13 to 14 doublings.

At a doubling time of 6 hours (typical for spoilage organisms at room temperature), this takes less than 4 days. At a doubling time of 8 hours, still less than 5 days. This is why foods left at room temperature spoil so quickly and why proper temperature control is critical.

What Stops Bacterial Growth

An often-cited thought experiment illustrates the impossibility of unlimited growth. Start with one E. coli cell at 37 degrees Celsius with unlimited nutrients.

After 24 hours (72 doublings), the population is 2 to the 72nd power, or 4.7 times 10 to the 21st cells. The volume of these cells is approximately 1,800 cubic meters. This is enough bacteria to cover a basketball court nearly 4 meters deep.

After 48 hours, the volume exceeds the volume of Earth itself by 1,000 times. Obviously impossible.

What prevents this catastrophic growth? The same factors that limit any biological system.

Nutrient depletion is the primary limiter. Bacteria need carbon (glucose), nitrogen (amino acids or ammonia), phosphorus, sulfur, and trace minerals. Any of these can become limiting. In fermented foods, glucose is typically the first to run out. Once depleted, LAB cannot continue fermenting rapidly.

Oxygen availability limits aerobic bacteria. If oxygen becomes depleted, aerobes slow dramatically or stop entirely. This is why fermentation uses the absence of oxygen strategically.

Waste accumulation becomes toxic. As bacteria metabolize, they produce organic acids, ethanol, and other compounds. When these reach critical concentrations, they inhibit further growth. In yogurt fermentation, the pH drops below 4.5 and further LAB growth stops.

Temperature changes inhibit or kill organisms. Heat denatures enzymes and disrupts cell membranes. Cold dramatically slows metabolism without killing (which is why fermentations slow at low temperature but do not stop).

Physical space and cell density also limit growth. As cell density increases, cells begin inhibiting each other through contact and chemical signaling.

Controlling Growth Through Environment

Understanding growth factors allows precise control. In fermentation, this is the art and science.

To promote beneficial bacteria (like in sauerkraut fermentation), create conditions favoring them: low temperature (18 to 22 degrees Celsius, ideal for LAB), sufficient salt (2 to 3 percent, inhibiting spoilage organisms), anaerobic conditions (submerged below brine), and rapid pH drop (through initial LAB dominance).

To prevent pathogenic bacteria, create hostile conditions: acidic pH (below 4.6 prevents Clostridium botulinum), high salt (above 12 percent prevents most pathogens), low temperature (below 5 degrees Celsius slows growth dramatically), low water activity (dried foods), or direct heat treatment (cooking).

Food safety authorities use these principles to establish guidelines. Refrigerate perishables below 5 degrees Celsius (slows spoilage and pathogens). Cook to 71 degrees Celsius minimum (kills most vegetative bacteria). Keep hot foods above 60 degrees Celsius (too hot for most pathogens). These simple rules work because they understand growth rate and limiting factors.

The Remarkable Efficiency of Bacteria

Despite their tiny size and simplicity, bacteria are phenomenally efficient. A single bacterial cell contains approximately 4 million proteins, each precisely folded and positioned. It can synthesize its own DNA, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids. It can sense its environment and respond to changes. It can communicate with other cells.

Most remarkably, it can divide into two identical cells in as little as 20 minutes under ideal conditions. Imagine if human mothers could produce a perfectly formed infant every 20 minutes. The population would be incomprehensible.

This efficiency is humbling. It reminds us that life at the microscopic scale operates according to principles we can understand and predict. It shows us that microorganisms are not chaotic or random but follow mathematical rules. And it demonstrates why respecting microbial growth is essential for food safety and fermentation success.