How Your Kitchen Can Become a Laboratory with Fermentation

Most people consume fermented foods every single day without understanding the elegant biochemistry happening at a microscopic level. That tangy yogurt sitting in your fridge, the complex flavors in your miso paste, the effervescent kombucha you sip in the afternoon, all the result of microorganisms following fundamental biochemical principles that have remained unchanged for billions of years.

Fermentation is not new. Humans have been fermenting foods for over 10,000 years, long before we understood microbiology or genetics. Yet only recently have scientists begun to fully appreciate the genius of what traditional cultures understood intuitively: fermentation is transformation through microbial metabolism.

What Is Fermentation, Really?

At its core, fermentation is a metabolic process where microorganisms break down sugars in the absence of oxygen, producing energy (ATP) along with various byproducts. These byproducts like lactic acid, acetic acid, and ethanol are what preserve the food, give it distinctive flavors, and create the health benefits we associate with fermented foods.

Unlike aerobic respiration (which requires oxygen and generates 30-38 ATP molecules per glucose), fermentation is a survival strategy. When oxygen runs out, bacteria and yeast face a crisis: they cannot regenerate NAD+, a crucial molecule needed for their primary energy-producing pathway called glycolysis. Fermentation solves this problem elegantly. It uses pyruvate (a byproduct of glycolysis) as the final electron acceptor, regenerating NAD+ so the energy-producing machinery can continue running.

This might sound abstract, but the results are tangible. One glucose molecule processed through fermentation produces only 2 ATP molecules compared to the 30-38 produced through aerobic respiration. Yet this is enough for microorganisms to survive, grow, and fundamentally transform food.

The Three Main Types of Fermentation

Different microorganisms produce different fermentation products, each creating unique flavors, aromas, and health benefits.

Lactic acid fermentation is what happens when lactic acid bacteria (LAB) like Lactobacillus plantarum or Leuconostoc mesenteroides colonize your vegetables. The equation is simple: one glucose molecule becomes two lactate molecules. The resulting lactic acid dramatically lowers the pH, creating an acidic environment where pathogens cannot survive. This is why sauerkraut, kimchi, and many traditional vegetable fermentations rely on LAB. The rapid acidification creates a self-preserving food that can last months or even years.

Alcoholic fermentation is what yeast like Saccharomyces cerevisiae does. One glucose becomes two ethanol molecules plus carbon dioxide. The ethanol is antimicrobial (it kills bacteria), which is why fermented beverages with alcohol were historically safer than water. The CO2 creates carbonation and helps leaven bread by creating tiny air pockets. This single microorganism transformed human civilization by making drinking water safe and enabling bread production.

Acetic acid fermentation is performed by acetic acid bacteria like Komagataeibacter xylinum. These organisms take ethanol (from yeast) and oxidize it into acetic acid. This is how vinegar is made. Kombucha combines all three: yeast ferments sugar into ethanol and CO2, then bacteria oxidize that ethanol into acetic acid, creating a complex flavor profile and preservation system.

Why Temperature and Salt Matter

Understanding fermentation means understanding how to control the microorganisms doing the work. Temperature is one of the most important variables.

Lactic acid bacteria grow optimally between 20 and 45 degrees Celsius. Too cold and fermentation becomes extremely slow. Too hot and spoilage organisms may outcompete your beneficial bacteria. The sweet spot for vegetable fermentations is 18 to 22 degrees Celsius. At this temperature, LAB grow steadily, outcompeting pathogens through acid production while creating complex flavor development.

Salt serves multiple purposes. A 2 to 3 percent salt solution (20-30 grams per kilogram of vegetables) does three things: it draws water from the vegetables through osmosis, creating a brine that keeps them submerged; it inhibits the growth of spoilage organisms while LAB tolerate the salt quite well; and it creates an environment where the fermentation proceeds at a controlled pace. Too little salt and harmful microbes may flourish. Too much salt and LAB cannot grow efficiently.

What Makes Fermented Foods Healthy

The health benefits of fermented foods come from three sources: the metabolic byproducts of fermentation, the living microorganisms themselves, and the enhanced bioavailability of nutrients.

The organic acids produced during fermentation lower pH to below 4.0, creating an inhospitable environment for pathogens while preserving the food. Beyond preservation, these acids influence your gut health by feeding beneficial bacteria and promoting the growth of acidophilic (acid-loving) microorganisms.

The live microorganisms in unpasteurized fermented foods are true probiotics if they meet specific criteria: they must survive your stomach acid, reach your colon alive, and provide documented health benefits. Not all fermented foods contain living microorganisms (many are pasteurized), and not all microorganisms are probiotics. Recent research shows that certain strains of Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus plantarum, and various Bifidobacterium species reduce respiratory infections by 9 to 24 percent and prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhea in 37 percent of cases.

Beyond probiotics, fermentation increases the bioavailability of nutrients. Lactic acid bacteria produce enzymes like protease (which breaks down proteins) and phytase (which breaks down phytic acid). In vegetable fermentations, these enzymes enhance protein digestibility by breaking down antinutritional factors. In soy fermentations like tempeh and miso, this dramatically improves protein quality. Raw soybeans have a PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score) of 0.52 while fermented soy protein reaches 0.92, comparable to animal protein.

Starting Your Own Fermentation

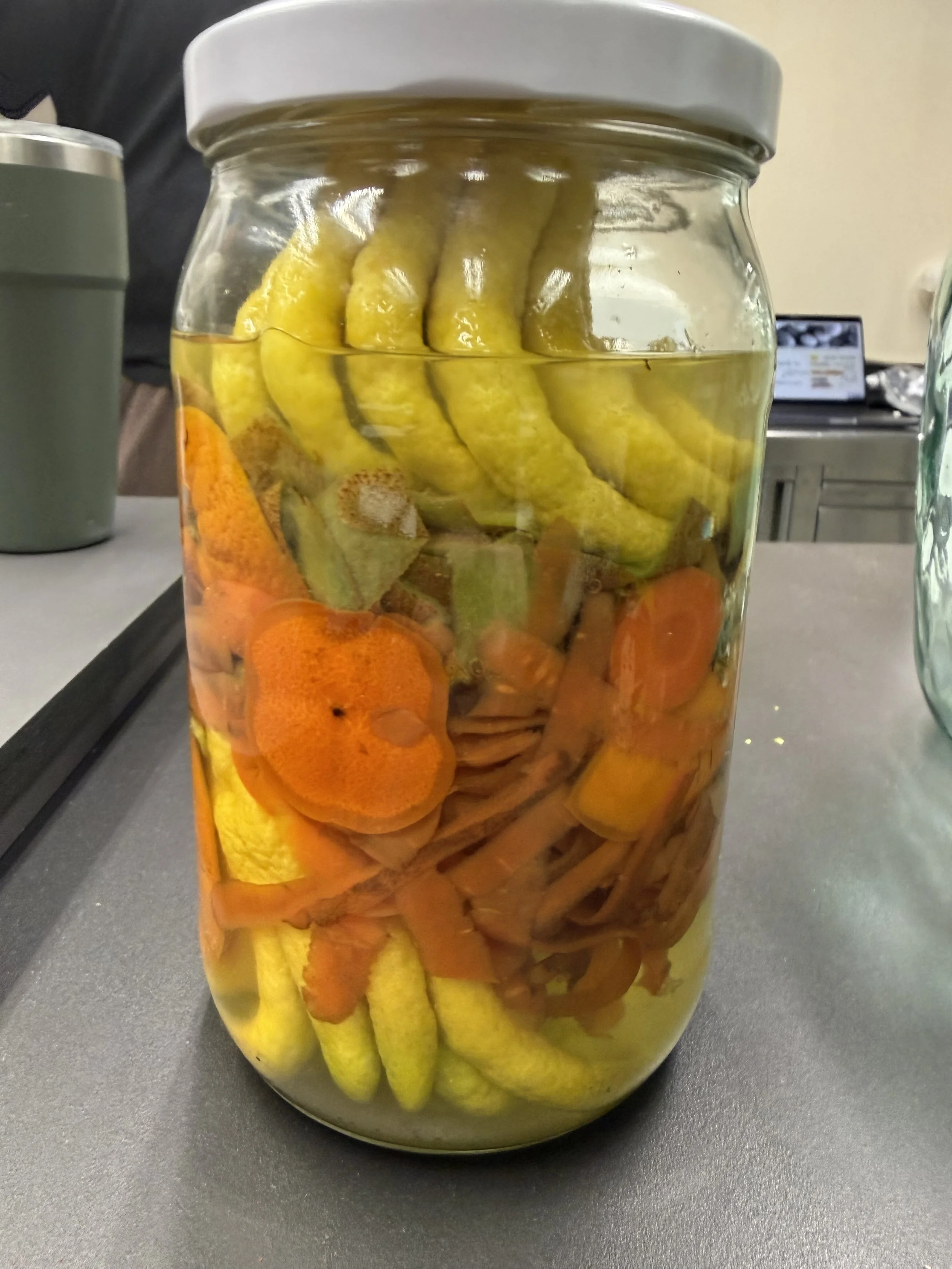

Beginning a fermentation is surprisingly simple. You need five things: fresh vegetables or dairy, salt, a container, proper temperature, and time.

Wash your vegetables thoroughly. Measure your salt: 2 to 3 percent of the vegetable weight. Mix them together in a clean glass jar. Pack the vegetables down firmly so they become submerged in their own juices. Cover with a cloth or use an airlock. Leave at room temperature (18-22 degrees Celsius) and wait.

What happens next is remarkable. Within 24 hours, you will see tiny bubbles forming (carbon dioxide from bacterial respiration). Within 3 days, the brine becomes cloudy (bacterial cells) and the smell changes from fresh to tangy. Within a week, the pH drops below 4.0 (measured with pH strips), the vegetables become softer, and complex flavors develop.

The microorganisms doing this work are not dangerous. They are using the same biochemical pathways that have worked for millions of years. Lactobacillus plantarum, for example, is so safe it is sold as a probiotic supplement. The acidic environment it creates is hostile to pathogens like E. coli or Salmonella. This is why fermented foods are among the safest foods you can eat.

The Broader Significance

Fermentation represents something profound about life itself. Microorganisms are not our enemies; they are not passive victims of our immune system. They are sophisticated chemists, following the laws of biochemistry to create the exact molecules that benefit human health.

When you eat fermented foods, you are consuming the products of millions of years of microbial evolution. You are feeding your gut with molecules that feed beneficial bacteria. You are ingesting living microorganisms that have survived countless environmental challenges.

In a world of processed foods, artificial probiotics, and sterilized everything, fermentation offers an alternative. It offers complexity, safety, and nutrition from simple ingredients and time. It offers proof that you do not need laboratories and chemical synthesis to create health. You just need to understand how to work with the living world rather than against it.

Your kitchen can become a laboratory. Not through complicated equipment or dangerous chemicals, but through harnessing the power of microorganisms to do what they have done for ten thousand years: transform simple ingredients into food that preserves, nourishes, and heals.