The Magic of Miso: Ancient Fermentation Meets Modern Science

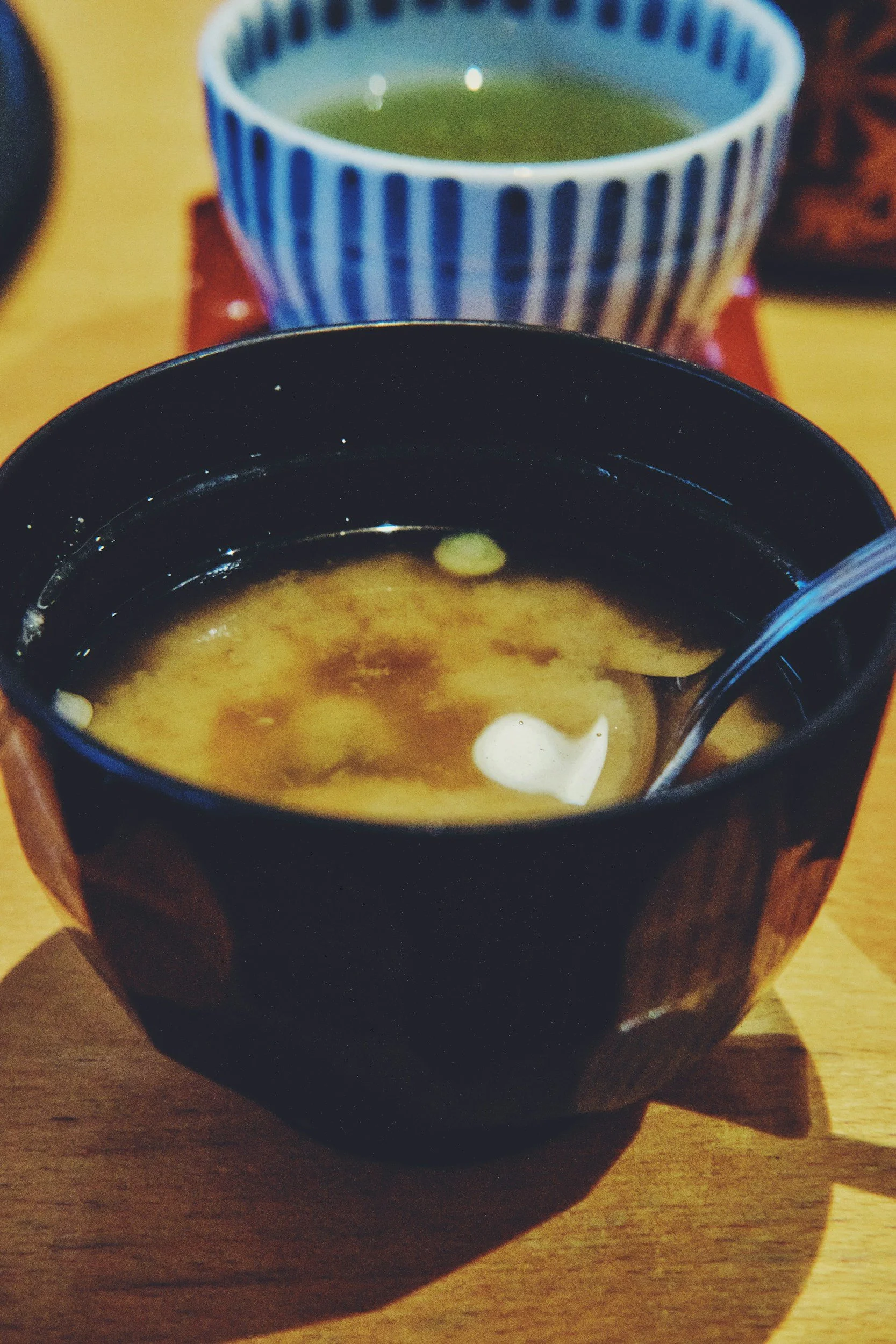

In Japanese cuisine, miso is often described as liquid gold. A spoonful contains the concentrated complexity of flavors, aromas, and health benefits that result from years of microbial fermentation. Yet what makes miso truly remarkable is not poetry but biochemistry.

Miso represents one of humanity's oldest and most sophisticated fermentation processes. It demonstrates how microorganisms, salt, time, and human knowledge combine to transform simple soybeans into a food that improves nutrition, creates addictive umami flavors, and supports health.

Traditional miso begins with soybeans. These beans, in their raw form, are difficult to digest and contain antinutritional compounds that prevent nutrient absorption. Through fermentation, these problems are solved.

The process starts with cooking soybeans until soft. This breaks down some resistant compounds and reduces antinutrients slightly. The cooked soybeans are then mixed with koji, the fermented grain culture. Koji is made by cultivating Aspergillus oryzae (a fungus) on grain, typically barley or rice.

Aspergillus oryzae produces powerful enzymes including amylase (which breaks down starch) and protease (which breaks down proteins). When koji is mixed with cooked soybeans and salt (approximately 12 to 15 percent by weight), the fermentation begins.

This mixture, called miso paste, is then packed into containers and stored. The fermentation can last anywhere from a few weeks (for commercial quick-fermented miso) to three to five years for traditional miso.

During this fermentation, multiple microbial communities work in succession. Aspergillus oryzae initially dominates, producing its powerful enzymes. As the fermentation progresses, lactic acid bacteria like Lactobacillus plantarum and Leuconostoc mesenteroides colonize the miso. Finally, yeast species may contribute to final flavor development.

The chemistry of miso fermentation is the chemistry of protein and carbohydrate breakdown. Amylase from Aspergillus oryzae breaks starches into sugars. Protease breaks proteins into amino acids and peptides. This enzymatic activity creates the foundation for flavor development.

The resulting amino acids, particularly glutamate, are the basis for umami flavor. Glutamate binds to umami taste receptors on your tongue, creating the savory sensation that is uniquely satisfying. High-quality, long-fermented miso contains remarkably high concentrations of free glutamate, sometimes exceeding 1000 parts per million.

Additionally, the proteolytic activity breaks down antinutritional factors like phytic acid and protease inhibitors. Phytic acid binds minerals like zinc and iron, preventing absorption. By breaking it down, fermentation enhances mineral bioavailability.

The salt content (12 to 15 percent) serves multiple purposes. It inhibits spoilage organisms while LAB tolerate salt well. It extracts water from the beans through osmosis, creating a concentrated paste. And it preserves the miso indefinitely, allowing it to develop complex flavors over years.

The duration of miso fermentation profoundly affects flavor and composition. Quick commercial miso, fermented for weeks using rapid fermentation techniques, tastes milder and fresher. Traditional miso, fermented for years, develops deep, complex flavors and darker color.

The darker color results from enzymatic and non-enzymatic browning reactions. As amino acids react with sugars at the high concentration in miso, they form brown polymers called melanoidins. These compounds give miso its rich brown color and contribute to its complex flavor and aroma.

Longer fermentation also increases the concentration of beneficial compounds. The amino acid tyrosine can be further metabolized by microorganisms into phenolic compounds with antioxidant properties. Peptides accumulate as proteins are slowly broken down. The overall complexity increases with time.

This is why traditional miso commands higher prices and is preferred by many chefs. The extended fermentation creates something that brief fermentation cannot replicate.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of miso fermentation is how completely it transforms soybean nutrition.

Raw soybeans have a protein digestibility corrected amino acid score (PDCAAS) of 0.52, meaning only 52 percent of their protein is available to your body in usable form. The remaining protein is bound by antinutritional compounds. Fermented soy products like miso achieve a PDCAAS of 0.92 or higher, comparable to animal protein sources like eggs and beef.

This occurs because fermentation:

Breaks down phytic acid through phytase enzyme activity, freeing bound minerals

Hydrolyzes proteins into dipeptides and amino acids that are more readily absorbed

Breaks down protease inhibitors that prevent protein digestion

Creates free amino acids that are immediately bioavailable

Produces B vitamins through microbial synthesis, particularly B1, B2, B3, and B12

The mineral bioavailability in miso is dramatically higher than in raw soybeans. Iron, zinc, and calcium that were bound by phytic acid become available. This is why fermented soy products are more nutritious than raw or cooked soy products.

Traditional miso contains living microorganisms. These include Lactobacillus plantarum, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, and various yeast species. When miso is consumed in its raw state (added to soup after cooking to preserve microorganisms), these live cultures may provide probiotic benefits.

Key point: heating miso (boiling it in soups) kills these microorganisms. While the enzymes and fermentation products remain, the live cultures do not. For maximum probiotic benefit, add miso after cooking.

Not all commercial miso contains viable microorganisms. Heat-treated or pasteurized miso lacks living cultures. Quality producers specifically note when their miso contains live cultures.

The most beneficial miso is unpasteurized, traditionally fermented miso added to foods after cooking. This preserves both the living cultures and all the fermentation products.

The diversity of miso varieties can seem overwhelming. Different regions of Japan produce distinctive styles.

Hatcho miso is fermented entirely from soybeans without grain koji, resulting in intense umami and deep color. It ferments for at least two to three years.

Mugi miso uses barley koji as the primary ingredient, creating a sweeter, lighter flavor. It is faster to ferment, typically one to two years.

Shiro (white) miso contains a higher proportion of grain koji and ferments for the shortest time (weeks to months), resulting in mild, sweet flavor.

Awase miso is a blend of different misos, creating balanced flavor.

When selecting miso, look for these indicators of quality: long fermentation time (2+ years listed on label), no added alcohol or preservatives, unpasteurized or raw status, and recognition from Japanese origin (particularly if labeled as traditionally made).

Use miso to finish soups, sauces, and dressings rather than cooking it extensively. Add it to boiling water just before serving. Combine it with other umami ingredients like mushrooms or tomatoes. Use it to season marinades, dressings, and broths.

Integrating miso into your diet is simple. A teaspoon of miso in warm water creates a morning broth. A tablespoon of miso whisked into salad dressing creates umami depth. Miso in braising liquid for vegetables or grains adds complexity.

The traditional Japanese breakfast soup, miso soup, is an excellent introduction. It is simple to prepare: heat kombu (seaweed) broth, remove kombu, dissolve miso in a small amount of cold broth, add the mixture to hot broth, and serve with tofu and vegetables.

Miso shines in vegetable braises, grain bowls, and sauces. It pairs remarkably well with mushrooms (both high in umami), creating deeply satisfying dishes.

Most importantly, miso reminds us of something crucial: fermentation is not modern health optimization. It is ancient wisdom proven by centuries of safe consumption. Cultures that consumed fermented foods for thousands of years understood intuitively what modern science is now documenting: fermentation improves nutrition, creates health benefits, and produces foods that satisfy deeply.

When you consume miso, you are consuming the result of microbial intelligence, enzymatic activity, and time. You are consuming a food that has been refined through thousands of years of human experience. That is not something to take lightly.