The Microbiology of Safe Fermentation: How to Harness Good Microbes and Avoid Hidden Risks

Fermentation enjoys a reputation as both ancient and "natural," which can lead to a dangerous misconception: that anything fermented is automatically safe. This is false. Fermentation is indeed a powerful safety technology, one that has protected food for millennia, but it works only when conditions favor beneficial microbes and actively suppress harmful ones.

This article explains, in practical and evidence-based terms, how safe fermentation works, where the genuine risks lie, and what controls distinguish a health-promoting fermented food from a microbiological hazard.

Why Fermented Foods Are Usually Safer Than Raw Ingredients

Raw ingredients arrive contaminated. Milk from the udder, cabbage from the field, meat from slaughter, grains from harvest…all carry whatever microbes happened to colonize them: soil bacteria, environmental yeasts, human-associated organisms, and occasionally pathogens.

During a successful fermentation, a carefully chosen or naturally selected consortium of microorganisms grows exponentially faster than everything else. As these beneficial microbes proliferate, they engineer an inhospitable environment for competitors and pathogens through multiple mechanisms:

pH drops sharply. Lactic acid bacteria convert sugars into lactic acid; acetic acid bacteria produce acetic acid. The resulting acidity inhibits most foodborne pathogens.

Water activity (aw) decreases. When salt or sugar is added, "free" water: the water available to microbes for growth, becomes bound, reducing the environment's hospitality to most organisms.

Ethanol and CO₂ accumulate in alcoholic and mixed fermentations, creating additional selective pressure.

Nutrients are monopolized. Beneficial microbes consume available sugars and other substrates, leaving little for late arrivals or slow growers.

Antimicrobial compounds appear. Certain lactic acid bacteria produce bacteriocins, ribosomally synthesized peptides that kill or inhibit competing bacteria. Nisin, produced by Lactococcus lactis, is the most studied example and demonstrates potent activity against Gram-positive pathogens including Listeria monocytogenes.

This orchestrated transformation is why properly fermented sauerkraut, yogurt, aged cheeses, dry salamis, and vinegars are microbiologically safer than their raw starting materials. Classic foodborne pathogens (Salmonella, E. coli O157, Campylobacter) struggle or fail entirely once pH, water activity, and microbial competition shift beyond their tolerance range.

GRAS and QPS: What "Safe Microbes" Mean in Regulation

Regulatory bodies recognize that not all microbes are equal. Two formal frameworks assess microbial safety for food use:

GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) is used in the United States and applies to specific strains and specific applications. GRAS status requires either a history of safe use prior to 1958 or scientific evidence equivalent to that needed for food additive approval.

QPS (Qualified Presumption of Safety) is the European Union's harmonized approach. QPS status applies to taxonomic units, typically at the species level for bacteria and yeasts, that demonstrate a documented history of safe use, lack acquired antibiotic resistance, and carry no hazardous traits.

Both frameworks facilitate faster approval for well-characterized organisms while mandating full safety assessment for novel or poorly understood microbes.

Examples of microorganisms with QPS or GRAS status include:

Using these well-characterized organisms as defined starter cultures, under validated conditions, differs fundamentally from uncontrolled microbial growth. Their behavior is predictable, their safety extensively documented, and their performance consistent.

Starters vs Wild Fermentations: Two Philosophies, Different Risk Profiles

From a microbiological perspective, fermentations fall into two categories distinguished by how microbial communities assemble.

1. Wild or Spontaneous Fermentation

Here, microorganisms arrive from raw materials, the environment, previous batches, or mixed "mother" cultures. The microbial community self-assembles based on ecological competition and environmental conditions.

Examples:

Kefir grains (consortia of lactic acid bacteria, acetic acid bacteria, and yeasts embedded in a polysaccharide-protein matrix)

Kombucha SCOBYs (symbiotic cultures dominated by Brettanomyces yeasts and Komagataeibacter acetic acid bacteria, though composition varies)

Spontaneous vegetable fermentations (sauerkraut, kimchi)

Sourdough starters (typically containing 3 lactic/acetic acid bacteria and 1 yeast species per starter; composition shaped by maintenance practices rather than geography)

Advantages:

No dependence on industrial suppliers

Rich microbial diversity yielding complex flavors

Deep cultural and artisanal significance

Disadvantages:

Microbial composition can drift over successive generations

Batch-to-batch inconsistency in acidification rate and sensory properties

Difficult to validate safety through standard microbiological testing

Greater sensitivity to hygiene lapses, temperature deviations, and contamination

Risk of accumulating undesirable organisms, including potential pathogens

Research on commercial kombucha revealed surprising microbial diversity: while beneficial Brettanomyces and Komagataeibacter typically dominate, some products contain enteric bacteria including E. coli and Bacteroides thetaiotamicron, likely introduced through contamination. Similarly, kefir grains sourced from traditional producers have tested positive for coliform bacteria and pathogens when hygiene standards lapse.

2. Defined Starter Cultures

Here, one or several characterized strains (isolated, genetically identified, and industrially propagated) are inoculated into prepared substrate (pasteurized milk for yogurt, meat batter for salami) in known concentrations.

Advantages:

Consistent, predictable acidification kinetics and sensory profile

Easier to demonstrate safety to regulators and consumers

Less vulnerable to contamination if handled correctly

Reproducible across production batches

Disadvantages:

Lower microbial diversity, sometimes yielding less complex flavors

Dependence on cold chain and supplier reliability

Vulnerability to bacteriophages: viruses that infect bacteria

Bacteriophages represent one of the dairy industry's most persistent challenges. These viruses infect starter culture bacteria, causing fermentation to slow or fail entirely. Phage contamination can originate from raw milk, equipment, air, or even the starter culture itself if strains carry lysogenic prophages (integrated viral DNA) that spontaneously activate. Modern starter culture management involves phage-resistant strain rotation and maintaining diverse culture banks.

Whether using wild or defined systems, safety ultimately depends on environmental controls and process discipline. A well-managed spontaneous fermentation can be safe; a poorly executed defined-culture fermentation can fail.

The Three Foundational Control Levers

Across all fermentation systems, three environmental factors determine whether beneficial or harmful microbes prevail.

1. pH (Acidity): The Primary Safety Barrier

Most foodborne pathogens cannot grow below pH 4.6, a threshold established through decades of food safety research. This critical value became the regulatory demarcation between low-acid and acidified foods in the United States.

Pathogen-specific pH limits:

Salmonella spp. 3.8; E. coli O157: H74.4; Listeria monocytogenes 4.4–4.6 (strain-dependent); Clostridium botulinum (Group I, proteolytic) 4.6–4.8.

However, pH alone does not guarantee safety. C. botulinum can, under specific conditions (particularly in protein-rich media such as those containing ≥3% soy or milk protein) grow and produce toxin at pH values below 4.6. Additionally, Listeria monocytogenes exhibits remarkable acid tolerance: it can survive (though not thrive) at pH 4.4 and can adapt to acid stress through multiple physiological mechanisms, making it a persistent concern in ready-to-eat fermented products.

Target pH for safety: Most successful vegetable fermentations naturally finish between pH 3.4 and 4.0, comfortably below the pathogen threshold. For dairy fermentations, pH 4.6 or lower within 48 hours is the standard safety criterion.

The importance of rapid acidification: Pathogens present in raw materials can multiply during the lag phase before beneficial microbes establish dominance. Reaching target pH quickly, (typically within 24–48 hours for vegetables, 4–12 hours for yogurt) minimizes this window of vulnerability. This is why temperature control, adequate salt, and active starter cultures matter: they accelerate the beneficial microbes' growth and acid production.

2. Water Activity (aw): Controlling Microbial Hydration

Water activity measures the "free" water available to microbes, water not bound to salts, sugars, or other solutes. The scale ranges from 0 (bone-dry) to 1.0 (pure water).

Pathogen water activity requirements:

Most bacterial pathogens: 0.94–0.95; Clostridium botulinum ~0.93–0.94; Staphylococcus aureus 0.83–0.86.

Staphylococcus aureus tolerance of low water activity poses a specific risk: it can grow and produce heat-stable enterotoxins in moderately salted environments where other pathogens fail. Enterotoxin production occurs at water activities as low as 0.864–0.867 at 30°C, though higher temperatures and lower water activities further inhibit toxin synthesis.

Practical application in fermentation:

In fermented vegetables and meats, salt serves dual functions: it draws moisture from plant cells through osmosis (creating brine) and lowers water activity to inhibit undesirable microbes while favoring salt-tolerant lactic acid bacteria.

Recommended salt concentrations for vegetable fermentation:

Standard safe range: 2–3% salt by total weight (vegetables + water)

2% minimum: Below this, risk of pathogen survival increases unless validated starter cultures and calcium chloride are added

Calculation method: Weigh vegetables and water together, multiply by 0.025 (for 2.5%), and add that mass in salt. This consistently yields ~2.44% total salt concentration

For comparison, traditional recipes vary: sauerkraut typically uses 2.25–2.5% salt, low-salt pickles 3–5%, and traditional high-salt pickles 5–16%. Olives and umeboshi plums require 10% salt due to their specific microbiology and texture requirements.

3. Temperature: The Pace of Microbial Competition

Temperature governs microbial metabolism rate, determining how quickly beneficial microbes acidify the medium and how rapidly pathogens might multiply if conditions favor them.

Optimal fermentation temperature ranges:

Vegetable ferments 18–25°C (64–77°F); Balances LAB growth rate with flavor development

Yogurt42–46°C (108–115°F) Optimal for thermophilic S. thermophilus and Lactobacillus species

Temperate-climate spontaneous ferments18–24°C

Ambient temperature range in traditional fermentation regions

Temperature deviations and their consequences:

Too low (<15°C for vegetables, <36°C for yogurt): Beneficial microbes grow slowly, acidification lags, and the fermentation may take days longer than expected. Critically, if acidification is too slow, pathogens present in raw materials may multiply before pH drops to safe levels.

Too high (>30°C for vegetables, >46°C for yogurt): Fermentation proceeds rapidly but can produce off-flavors. More dangerously, heat-tolerant spoilage organisms or pathogens may proliferate, or beneficial cultures may die, halting acidification.

Special consideration for Listeria monocytogenes: This psychrotrophic (cold-tolerant) pathogen grows across an extraordinary temperature range: -0.4°C to 45°C. It can proliferate in refrigerated foods if other barriers (pH, salt, competing microflora) are inadequate, making it a persistent concern for ready-to-eat fermented products stored under refrigeration.

Practical guideline: Use a thermometer. Maintain fermentation within the recommended range for your product. For home yogurt-makers, a temperature-controlled yogurt maker or Instant Pot provides the stable 42–44°C environment that thermophilic cultures require.

Real Risks: Where Fermentation Safety Can Fail

Fermentation is not risk-free. Understanding where and how hazards arise allows for targeted prevention.

1. Biogenic Amines: The Hidden Chemical Hazard

Biogenic amines form when amino acid decarboxylase enzymes—produced by certain lactic acid bacteria—cleave amino acids' carboxyl groups, producing amines. This typically occurs late in fermentation, after fermentable sugars are exhausted and bacteria begin metabolizing amino acids for energy.

Toxic dose thresholds: Histamine and tyramine levels exceeding 100 mg/kg in food are considered potentially toxic; phenylethylamine exceeds safety thresholds above 30 mg/kg. However, individual sensitivity varies dramatically, and histamine-intolerant individuals may react to much lower levels.

Who is most vulnerable?:

Histamine-intolerant individuals: Genetic variations or gut damage can reduce activity of diamine oxidase (DAO) and histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT)—the enzymes that degrade histamine. When histamine accumulates, symptoms mimic allergies: skin rashes, hives, migraines, nasal congestion, digestive upset, fatigue, rapid heartbeat.

Patients taking MAO inhibitor (MAOI) medications: Monoamine oxidase normally degrades tyramine in the gut wall and liver. MAOIs irreversibly inhibit this enzyme, allowing dietary tyramine to enter systemic circulation, where it triggers norepinephrine release. The result: rapid, potentially fatal blood pressure spikes—the "cheese reaction" first documented in the 1960s. MAOI patients must avoid aged cheeses, fermented meats, soy sauce, miso, and other tyramine-rich foods.

Control strategies:

Use defined starter cultures selected for absence of amino acid decarboxylase activity

Limit fermentation time to prevent extended amino acid metabolism

Maintain strict hygiene to prevent contamination by decarboxylase-positive spoilage bacteria

In commercial settings, monitor biogenic amine levels in aged products

Emerging approach: Use bacteriocin-producing cultures (e.g., nisin) to inhibit amine-producing bacteria

2. Stress-Tolerant Pathogens: Microbes That Don't Play by the Rules

While most pathogens succumb to low pH, high salt, or cold temperatures, a few demonstrate exceptional resilience.

Listeria monocytogenes: The Psychrotrophic Survivor

L. monocytogenes violates nearly every assumed safety barrier:

Temperature range: -0.4°C to 45°C (can grow in your refrigerator)

pH tolerance: 4.6 to 9.5 (survives in moderately acidic and alkaline environments)

Salt tolerance: Grows in up to 20% NaCl (tolerates brines that stop most bacteria)

Water activity tolerance: Survives at aw < 0.90

This adaptability stems from sophisticated stress-response systems: acid tolerance mechanisms involving glutamate decarboxylase, osmotic stress response through compatible solute uptake, and alkaline adaptation through proton retention. Exposure to sublethal stress—moderate acid, moderate salt—can actually increase Listeria's virulence gene expression and resistance to subsequent, more severe stress.

Where Listeria threatens fermented foods:

Soft and semi-soft cheeses, especially if made from raw milk or contaminated post-pasteurization

Ready-to-eat fermented meats if pH remains above 4.4 or recontamination occurs after fermentation

Fermented vegetables if hygiene is poor, salt concentration inadequate, or pH insufficiently low

Control measures:

Ensure pH drops below 4.4 within 24–48 hours

Combine low pH with adequate salt (aim for aw < 0.94)

Maintain sanitary processing environments to prevent post-fermentation contamination

Consider using nisin or other anti-listerial bacteriocins in high-risk products

Staphylococcus aureus: The Toxin Producer

S. aureus tolerates lower water activity than most pathogens (minimum aw 0.83–0.86) and can grow in environments where lactic acid bacteria struggle. The critical hazard: it produces heat-stable enterotoxins. Even if fermentation eventually reduces viable S. aureus cells, any enterotoxin produced beforehand persists, as it withstands cooking temperatures that would kill the bacterium itself.

Prevention:

Rapid acidification to pH <4.6 within hours, before toxin production begins

Adequate salt combined with low pH

Good hygiene to minimize initial contamination

Refrigeration if fermentation will be slow

Clostridium botulinum: The Anaerobic Spore-Former

C. botulinum spores survive cooking, freezing, and drying. They germinate and produce botulinum neurotoxin—one of the most potent biological toxins known—in low-acid, low-oxygen environments.

Critical control points:

pH below 4.6: The foundational barrier. Below this threshold, C. botulinum cannot grow or produce toxin (with the caveat that protein-rich substrates may permit growth at slightly lower pH)

Rapid acidification: Minimizes time in the danger zone (pH >4.6, anaerobic, room temperature)

Salt or water activity: At aw ≤0.94 or salt ≥10%, C. botulinum growth is inhibited

Fermentation does NOT destroy spores: If a ferment fails to acidify properly, or if ingredients contain spores and pH remains >4.6, botulism risk exists. This is why pH monitoring is non-negotiable in commercial fermentation and strongly recommended for home fermenters.

3. Spore-Forming Bacteria: The Survivors

Bacterial endospores are metabolically dormant structures capable of withstanding extreme heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemical stress.

Bacillus cereus: The Rice Reheating Risk

B. cereus spores contaminate rice, grains, and vegetables. Cooking does not kill them; it may even trigger germination (spore activation). If cooked rice sits at room temperature, surviving spores germinate, and vegetative cells multiply exponentially, producing emetic toxin (cereulide) or diarrheal enterotoxins.

Relevance to fermentation: B. cereus is inhibited by low pH and can be controlled by lactic fermentation, but fermented grain products must be carefully managed. One study showed that B. cereus spore germination was inhibited in fermented milk and fruit-flavored milk, suggesting that fermentation-derived acids and other antimicrobials can suppress this organism.

Control:

Refrigerate fermented grain products immediately (≤4°C prevents germination and growth)

Avoid room-temperature storage of cooked, fermented, or reheated grain dishes

Bacillus subtilis: The Natto Organism

B. subtilis is unique: while most spore-forming bacteria are considered hazards, specific B. subtilis strains used in natto production have QPS and GRAS status. Safety evaluations confirm that natto strains lack the toxin-encoding genes (hbl, nhe, bceT, entFM) found in B. cereus and demonstrate no hemolytic or lecithinase activity.

Regulatory qualifications: B. subtilis QPS status requires absence of toxigenic potential, confirmed at the strain level.

4. Mycotoxins: Toxic Mold Metabolites

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by certain mold species (most notably Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium) that exhibit hepatotoxic, nephrotoxic, immunosuppressive, or carcinogenic properties.

Key mycotoxins of concern:

Aflatoxins (especially aflatoxin B1): potent liver carcinogens produced by Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus

Ochratoxin A: kidney toxin produced by Aspergillus and Penicillium species

Patulin: neurotoxin in moldy apples and apple products

Critical property: Mycotoxins are heat-stable. Cooking, baking, or pasteurization does not destroy them. Prevention is the only effective control.

Mycotoxins in fermented foods:

Can pre-exist in contaminated raw materials (grains, beans, fruits)

May be produced during fermentation if toxigenic mold species contaminate the product

Some fermentation processes reduce mycotoxin levels; others may concentrate them or create favorable conditions for toxigenic mold growth

Role of lactic acid bacteria as "green preservatives": LAB produce organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, and other antimicrobial compounds that inhibit mold growth. Additionally, some LAB strains bind mycotoxins to their cell walls, sequestering and inactivating them. Fermented maize meal studies showed that Streptococcus lactis and Lactobacillus delbrueckii significantly reduced aflatoxin B1, zearalenone, and fumonisin B1 levels.

Special case: Aspergillus oryzae (Koji mold):

A. oryzae has GRAS status and has been used safely in soy sauce, miso, and sake production for centuries. However, safety depends on proper fermentation conditions:

Time limit: Fermentation must not exceed 3 days. Extended fermentation (>3 days) can trigger production of toxic secondary metabolites, including kojic acid and other compounds

Strain verification: A. oryzae is genetically very similar to A. flavus (aflatoxin producer); commercial strains have been selected for loss of aflatoxin-producing capacity

Practical prevention:

Source high-quality, properly stored raw materials

Maintain sanitary fermentation environments

Monitor ferments for visible mold growth

Discard products with fuzzy, colored mold growth (black, green, pink, red)

In commercial production, test for mycotoxins in aged or long-fermented products

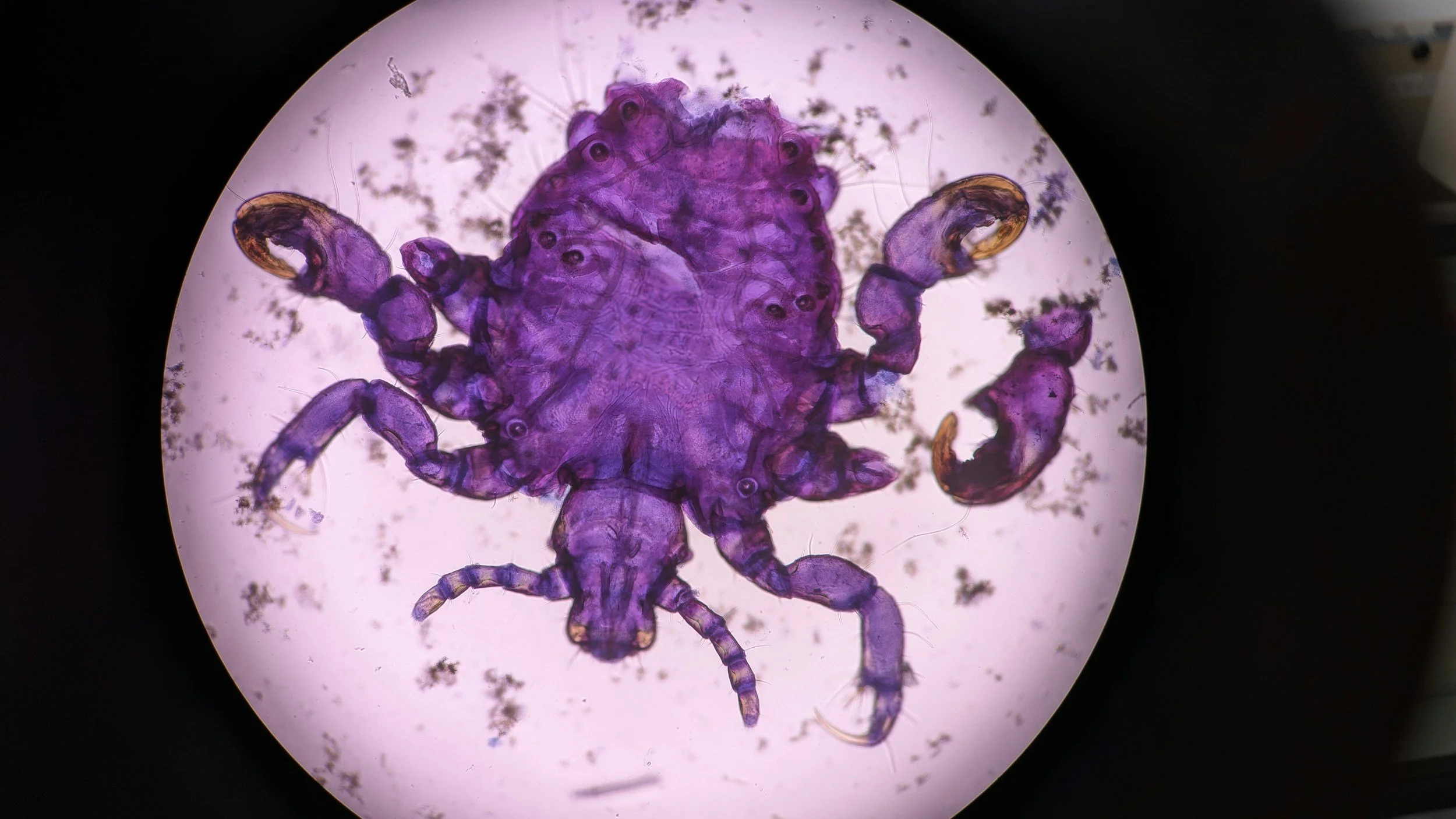

5. Parasites: Fermentation Alone Is Insufficient

Fermentation's antimicrobial effects target bacteria, yeasts, and molds. It does not reliably inactivate parasitic helminths (worms) or protozoa.

Trichinella spiralis (Trichinosis)

Trichinella larvae encyst in mammalian muscle tissue, particularly pork. Consumption of raw or undercooked infected meat causes trichinosis—a potentially serious parasitic infection.

Fermentation and Trichinella: A 2025 study on traditional fermented pork demonstrated that 5-day lactic acid fermentation failed to inactivate encysted T. spiralis larvae; viability was maintained throughout. This finding aligns with earlier curing studies showing that salt and acid alone do not reliably kill Trichinella.

Effective control measures:

Cooking: Internal temperature ≥71°C (160°F) throughout

Freezing: Specific time-temperature combinations for domestic pork (e.g., -15°C for 20 days, -23°C for 10 days)

Caution: Freezing is less effective for Trichinella species in wild game, which are freeze-resistant

For fermented meats: Traditional dry-cured sausages often combine fermentation with smoking or aging. Safety requires validation that processing achieves >96% Trichinella inactivation, typically through pH reduction below 5.2 combined with ≥1.3% salt and defined time-temperature exposure.

Anisakis spp. (Anisakiasis)

Anisakis larvae infect marine fish, particularly those that feed on krill. Human infection occurs when live larvae are ingested in raw or undercooked seafood.

Fermentation and Anisakis: Studies on salt-fermented squid and fish products show variable effectiveness. Traditional marination and cold smoking are often insufficient to inactivate larvae. The effect depends on salt concentration, pH, exposure duration, and product thickness—and few traditional processes have been rigorously validated.

Reliable control measures:

Freezing: -18°C or colder for ≥96 hours (EFSA recommendation)

Heating: 60–70°C for several minutes inactivates larvae

Practical implication: Fermented fish products—especially those consumed raw or lightly processed—require pre-treatment (freezing or heating) to ensure parasite inactivation. Fermentation alone cannot be relied upon.

Practical Guidelines for Safe Home Fermentation

Equipped with microbiological principles, home fermenters can apply evidence-based practices to maximize safety while preserving tradition and flavor.

1. Start with Clean, High-Quality Ingredients and Equipment

Why it matters: Initial microbial load determines the competitive landscape. Heavily contaminated raw materials give pathogens a head start.

Actions:

Wash vegetables thoroughly in potable water

Use pasteurized milk for dairy ferments unless you have advanced knowledge and trusted raw milk sources

Sanitize fermentation vessels, weights, airlocks, and utensils. Use boiling water, dilute bleach (rinse thoroughly), or food-grade sanitizers like StarSan

2. Use Adequate Salt

For vegetable ferments, salt is non-negotiable. It selectively inhibits pathogens and spoilage organisms while allowing salt-tolerant lactic acid bacteria to thrive.

Evidence-based salt recommendations:

Minimum safe concentration: 2% by total weight (vegetables + water)

Typical range: 2–3% for most vegetables

Higher salt for specific products: 3–5% for cucumbers; 10% for olives and umeboshi

Measurement precision matters: Salt types vary in density. One teaspoon of flake salt weighs ~1 g; one teaspoon of fine Himalayan salt weighs ~3 g. Using volume measurements without accounting for salt type can result in dangerously low salt concentrations.

Best practice: Weigh vegetables and water together. Multiply total weight by 0.025 (for 2.5% salt). Add that weight in grams of salt. This method guarantees consistent salinity regardless of batch size or vegetable type.

Exception: Below 2% salt, add a commercial vegetable starter culture and/or calcium chloride to prevent pathogen proliferation. Never go below 1% salt, even with a starter culture.

3. Exclude Air: Maintain Anaerobic Conditions

Lactic acid fermentation is anaerobic. Oxygen exposure at the surface invites mold growth and aerobic spoilage organisms.

Actions:

Keep vegetables fully submerged beneath brine

Use fermentation weights (glass, ceramic, or food-grade plastic)

Consider airlocks for long fermentations to allow CO₂ escape while preventing oxygen entry

If mold appears on the surface, carefully remove it along with a layer of underlying material. Smell and taste the remaining ferment; if it smells and tastes normal, it is likely safe. If widespread mold or off-odors/flavors are present, discard the batch

4. Control Temperature

Temperature precision accelerates beneficial microbes and suppresses competitors.

Target ranges:

Vegetable ferments: 18–24°C (64–75°F) ambient room temperature works well

Yogurt and thermophilic cultures: 42–44°C (108–111°F)—use a yogurt maker, Instant Pot, or temperature-controlled incubator

Monitoring: Use a kitchen thermometer. If room temperature is too cold, fermentation slows; if too hot, spoilage risk increases and cultures may die.

5. Reach Safe pH Quickly: and Verify It

Rapid acidification is the cornerstone of fermentation safety. The faster pH drops below 4.6, the narrower the window for pathogen growth.

Target pH:

Critical threshold: pH 4.6 or below

Safer target: pH 4.0 or below for vegetable ferments

Dairy products: pH 4.6 within 48 hours

How to measure pH:

Digital pH meters: Most accurate; calibrate regularly

pH test strips: Inexpensive, adequate for home use (ensure they measure to at least one decimal point)

What to do:

Test pH after 5–7 days for vegetables; after 4–12 hours for yogurt

If pH has not dropped to target, troubleshoot: Was salt concentration correct? Was temperature adequate? Was the starter culture active?

Do not consume ferments that fail to reach safe pH

6. Use Proven Starter Cultures When in Doubt

While wild fermentation has cultural and sensory appeal, defined starter cultures offer consistency and validated safety.

When to use starters:

Dairy ferments (yogurt, kefir, cultured buttermilk)

Fermented meats (salami, sausages)

First-time fermenters or risk-averse individuals

Sources: Purchase from reputable suppliers (e.g., cultures for health, Chr. Hansen, Lyofast). Follow manufacturer instructions for inoculation rate and temperature.

7. Do Not Over Age or Endlessly Reuse Wild Cultures

SCOBYs, kefir grains, and sourdough starters can accumulate mutations, bacteriophages, and contaminants over many cycles.

Best practices:

Periodically refresh wild cultures by discarding a portion and feeding/replenishing with fresh substrate

Monitor performance: If acidification slows, flavors change unexpectedly, or visible contamination appears, consider starting fresh

For sourdough: maintain a feeding schedule (daily for active starters, weekly for refrigerated starters)

8. Trust Your Senses, But Know Their Limits

Human senses evolved to detect spoilage, but they are not infallible.

Positive signs (healthy ferment):

Bubbles (CO₂ production indicates active fermentation)

Pleasant sour, tangy, or "pickled" aroma

Slightly cloudy brine (from bacterial growth)

pH below 4.6

Warning signs (spoilage or contamination):

Mold: Fuzzy patches, especially if black, green, pink, or red. White mold can also indicate spoilage unless it is part of a controlled fermentation (e.g., bloomy rind cheese)

Putrid, foul, or "off" odor: Not just tangy or funky, but genuinely unpleasant

Sliminess: Inappropriate texture changes, especially in vegetables

Gas production in the wrong context: E.g., excessive gas and bloating in a sealed vegetable ferment that should have completed fermentation

When in doubt, throw it out. No ferment is worth a foodborne illness.

9. Monitor Time: Temperature Abuse During Storage

Even successfully fermented products can spoil if stored improperly.

Guidelines:

Refrigerate finished ferments (≤4°C) unless they are shelf-stable due to very low pH, high salt, or other preservation factors

Avoid leaving fermented grain products (rice, porridge) at room temperature for extended periods—risk of B. cereus outgrowth

Consume refrigerated ferments within recommended timeframes (weeks to months, depending on product)

Who Should Exercise Extra Caution?

Fermented foods are generally safe for healthy adults, but certain populations face elevated risk.

Immunocompromised Individuals

People with weakened immune systems, due to HIV/AIDS, cancer chemotherapy, organ transplant immunosuppression, or primary immunodeficiency—are more susceptible to opportunistic infections from microbes that healthy immune systems easily clear.

Specific concerns:

Live microorganisms in unpasteurized fermented foods may pose infection risk

Translocation of even "safe" bacteria from the gut to bloodstream can occur if intestinal barriers are compromised

Recommendations:

Choose commercially produced, pasteurized fermented foods over homemade or unpasteurized artisanal products

Consult with healthcare providers before adding fermented foods to the diet

Pregnant Individuals

Pregnancy confers relative immunosuppression to prevent fetal rejection. This increases susceptibility to certain foodborne pathogens, particularly Listeria monocytogenes, which can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, or severe neonatal infection.

Guidance:

Avoid soft cheeses made from raw milk (Brie, Camembert, feta, queso fresco) unless labeled "made from pasteurized milk"

Exercise caution with refrigerated ready-to-eat fermented products (smoked fish, pâtés)

Pasteurized yogurt and hard cheeses are generally safe

Emerging evidence: Some studies suggest that consumption of certain fermented foods (yogurt, fermented milk) during pregnancy may reduce preterm birth risk and modulate maternal and infant gut microbiota beneficially. However, these benefits apply to validated, commercially produced products, not uncontrolled home ferments.

Infants and Young Children

Developing immune systems and immature gut barriers make infants more vulnerable to infection.

Considerations:

Introduce fermented foods cautiously, starting with small amounts of pasteurized yogurt

Avoid honey-fermented products for infants <12 months (botulism risk from honey, unrelated to fermentation)

Monitor for adverse reactions

Elderly Individuals

Age-related immune senescence and comorbidities (diabetes, renal disease) increase infection risk.

Recommendations: Similar to immunocompromised individuals, favor pasteurized, commercially produced fermented foods.

Histamine-Intolerant Individuals

Histamine intolerance arises when diamine oxidase (DAO) or histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT) enzyme activity is insufficient to degrade dietary and endogenously produced histamine.

Symptoms:

Migraines or headaches

Skin flushing, hives, itching

Nasal congestion, runny nose

Digestive upset (nausea, abdominal cramps, diarrhea)

Rapid heartbeat, palpitations

Fatigue

High-histamine fermented foods to limit or avoid:

Aged cheeses (Gouda, cheddar, Parmesan, blue cheese)

Fermented fish (anchovies, fish sauce)

Sauerkraut (despite its probiotic benefits)

Soy sauce, miso

Kombucha

Potential alternatives: Fresh, short-fermented yogurt may be better tolerated than aged products. Some LAB strains degrade histamine rather than produce it—seeking out products made with histamine-degrading cultures (e.g., certain Bifidobacterium strains) may help.

Patients Taking MAO Inhibitor Medications

MAOIs (used to treat depression) inhibit monoamine oxidase, the enzyme that degrades tyramine in the digestive tract. When tyramine from food enters systemic circulation unchecked, it triggers massive norepinephrine release, causing hypertensive crisis: sudden, severe blood pressure elevation that can result in stroke, heart attack, or death.

Tyramine-rich fermented foods to strictly avoid:

Aged cheeses (cheddar >6 months, Gouda, Parmesan, blue cheese, Stilton)

Fermented/cured meats (salami, mortadella, pepperoni, aged ham)

Soy sauce, miso, fermented bean curd (tofu)

Fish sauce, shrimp paste

Sauerkraut, kimchi

Tap beer, unpasteurized beer, red wine

Safe alternatives: Fresh cheeses (mozzarella, ricotta, cream cheese), fresh milk, pasteurized bottled beer in moderation.

Respect the Microbes and They Will Work for You

Safe fermentation is not mysticism; it is applied microbiology. The transformations that turn raw milk into tangy yogurt, cabbage into crisp sauerkraut, and soybeans into umami-rich miso are driven by predictable microbial ecology, governed by measurable environmental variables.

When you choose well-characterized microbes, or thoughtfully manage wild microbial communities, and control pH, salt concentration, temperature, and time, you engineer an ecosystem in which beneficial microbes flourish and pathogens are systematically excluded. The acid they produce, the antimicrobial compounds they secrete, and the competitive advantage they hold transform fermentation from a speculative gamble into a reliable preservation technology.

Conversely, when these controls are ignored or misunderstood, the same biological processes can permit harmful organisms to proliferate or allow toxic metabolites (biogenic amines, mycotoxins, pathogen-derived toxins) to accumulate.

The goal is neither to fear microbes nor to romanticize them, but to collaborate with them intelligently. This requires knowledge: understanding which microbes you want, which you must suppress, and which environmental levers create the conditions for success. It requires discipline: measuring salt accurately, monitoring pH reliably, maintaining temperature consistently, and recognizing when a ferment has failed. And it requires humility: acknowledging that some products, fermented meats, fish, low-salt innovations, carry inherent risks that demand extra validation, whether through laboratory testing, established recipes, or both.

With microbiological understanding and process discipline, fermented foods can indeed be among the safest, most nutritious, and most rewarding foods on the table. Respect the microbes, control the environment, verify the results, and they will work for you, not against you.